At the beginning of 2025, I spent 20 days in Japan. Though not a long period, it was enough to leave me with vivid and lasting impressions of the country.

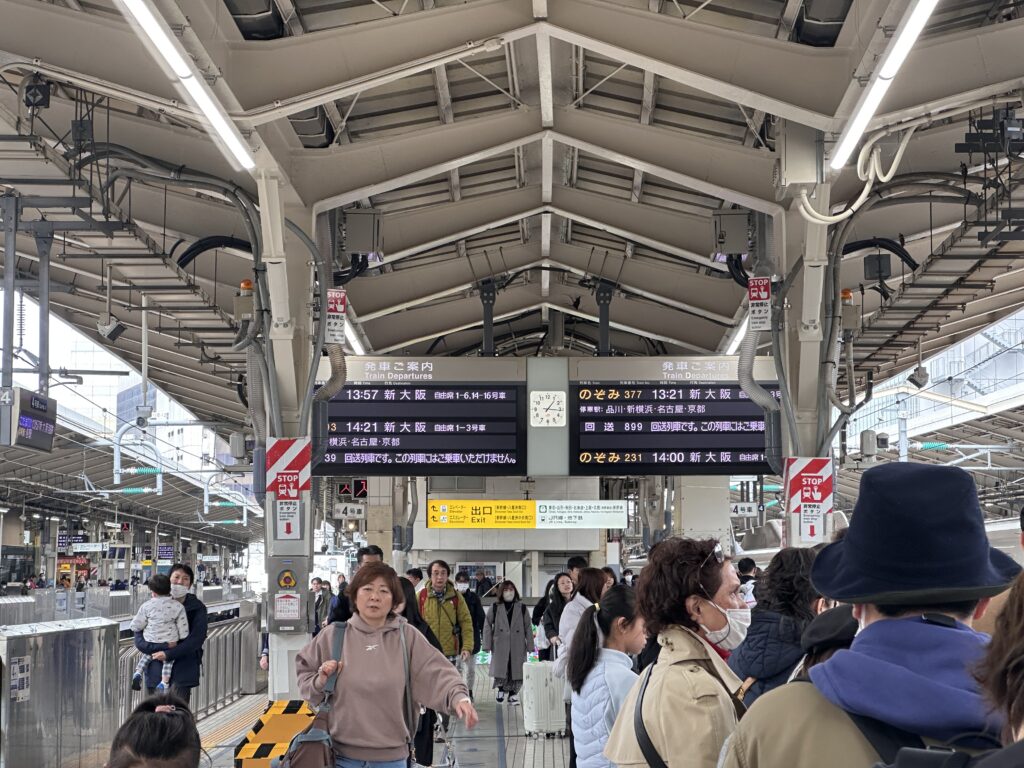

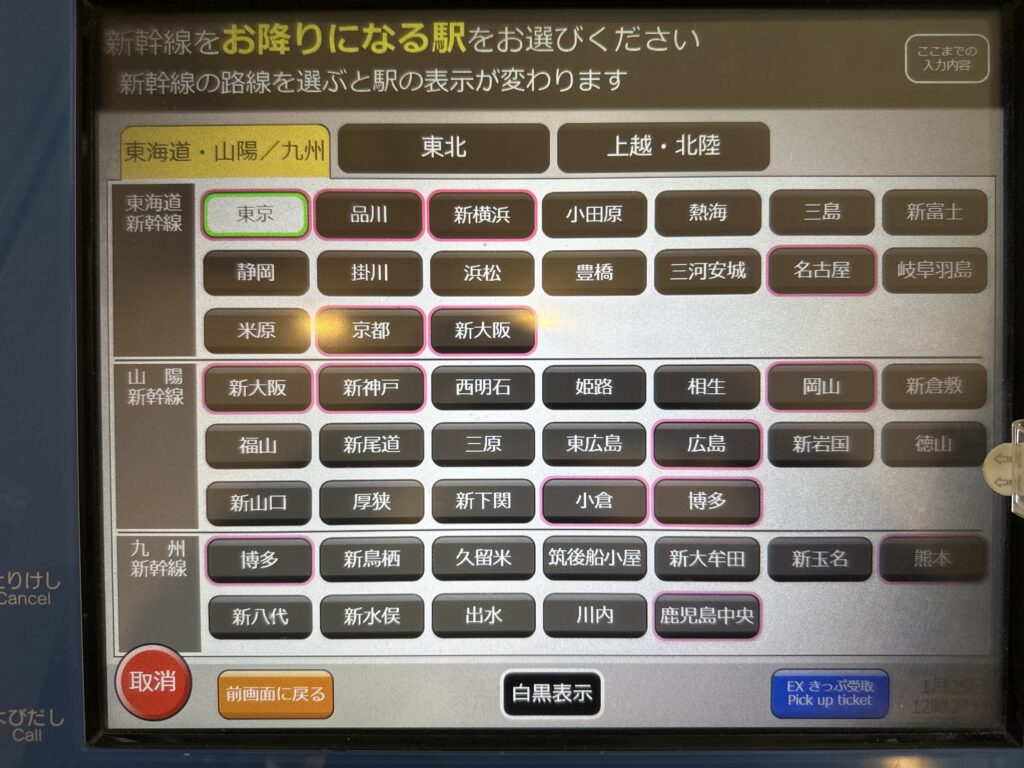

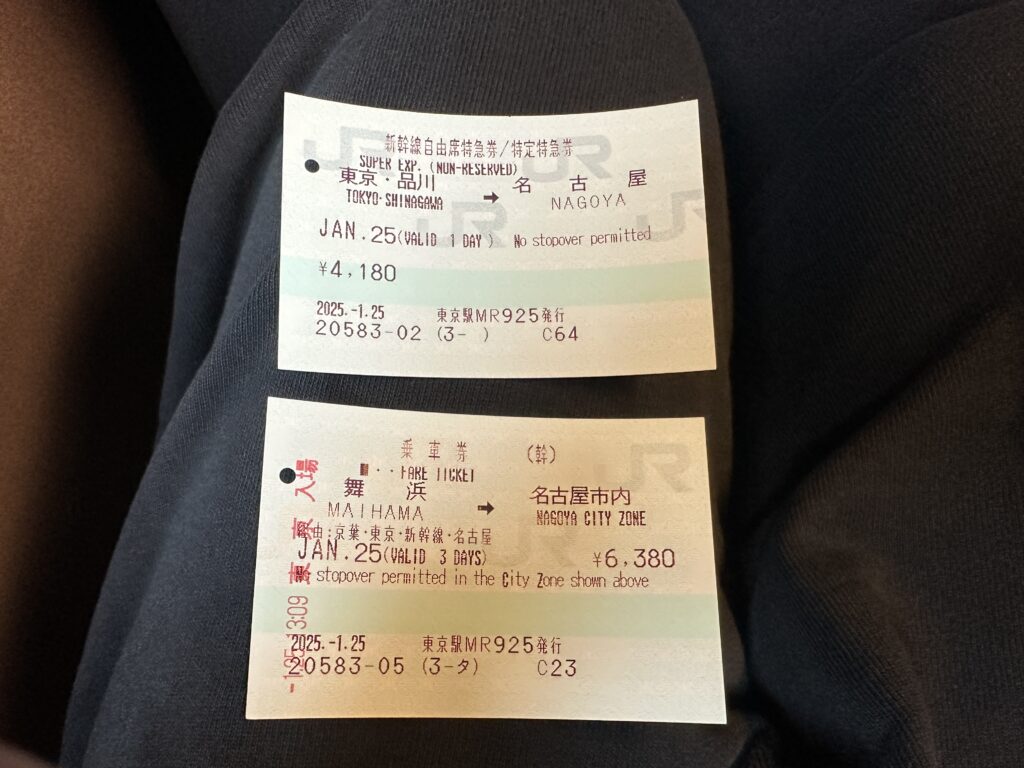

On our way from Tokyo to Nagoya, we experienced the Shinkansen for the first time. It is a kind of train, but the dense train schedules, complex platforms, and language barrier made us take the wrong exits several times. Even by the end of our stay, I still hadn’t fully understood why sometimes two tickets were required and sometimes only one. Later I learned that one is the “basic fare ticket,” and the other is the “limited express ticket.” Together, they complete a Shinkansen journey. This split-ticket system was confusing at first, but it reflects the meticulous and layered nature of Japan’s public transportation.

Outside the central districts of Tokyo or Osaka, most of Japan is made up of low-rise housing. During our stay in Nagoya’s suburbs, we lived in a detached house (known as ikkodate), and experienced the traditional style of living. These houses are often built with wooden frames, with sliding doors or partitions separating rooms, and tatami mats laid over slightly elevated floors. This design helps with insulation in winter and ventilation in summer, while also offering resilience against earthquakes. Living in such a house felt simple and close to nature, though it does have drawbacks, especially in terms of soundproofing and fire resistance.

One of my habits during travel is visiting local supermarkets and markets. In Japan, fresh produce is relatively expensive and available in fewer varieties compared to other countries. A single head of lettuce, for example, can cost nearly 300 yen. Price tags in supermarkets clearly show both the item price and the 8% consumption tax, so customers can see exactly what they are paying. This is more straightforward and transparent than in many countries where sales or value-added taxes are included directly in the product price without being itemized on the bill.

The streets of Japan left me deeply impressed. Trash cans are rarely seen along the roads, yet the streets remain remarkably clean. The government enforces strict waste-sorting rules: burnable waste, non-burnable items, PET bottles, and cans must be disposed of on designated collection days. Residents follow these rules meticulously, neatly bagging their trash and often covering it with nets to prevent scattering.

This same sense of order extends to vehicles parked on the streets. Whether it is an old Mercedes 230E or a retrofitted van, cars are strikingly clean and well-kept. It almost seems as if they had just left a showroom. This is partly cultural, as cleanliness is seen as a social courtesy, and partly institutional, with mandatory car inspections ensuring maintenance. Japan’s relatively dust-free environment and paved parking lots also contribute to this. Together, these elements create a public space that feels orderly and almost obsessively neat.

Japan is a nation constantly balancing tradition with modernity, precision with complexity, and personal freedom with social order. Experiencing this firsthand gave me not only a deeper understanding of Japan but also new perspectives on how rules, order, and daily life intertwine.